PHOTOGRAPHY AS AN EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITY

Research and excerpts from MA thesis project in Art Education, 2000-2002

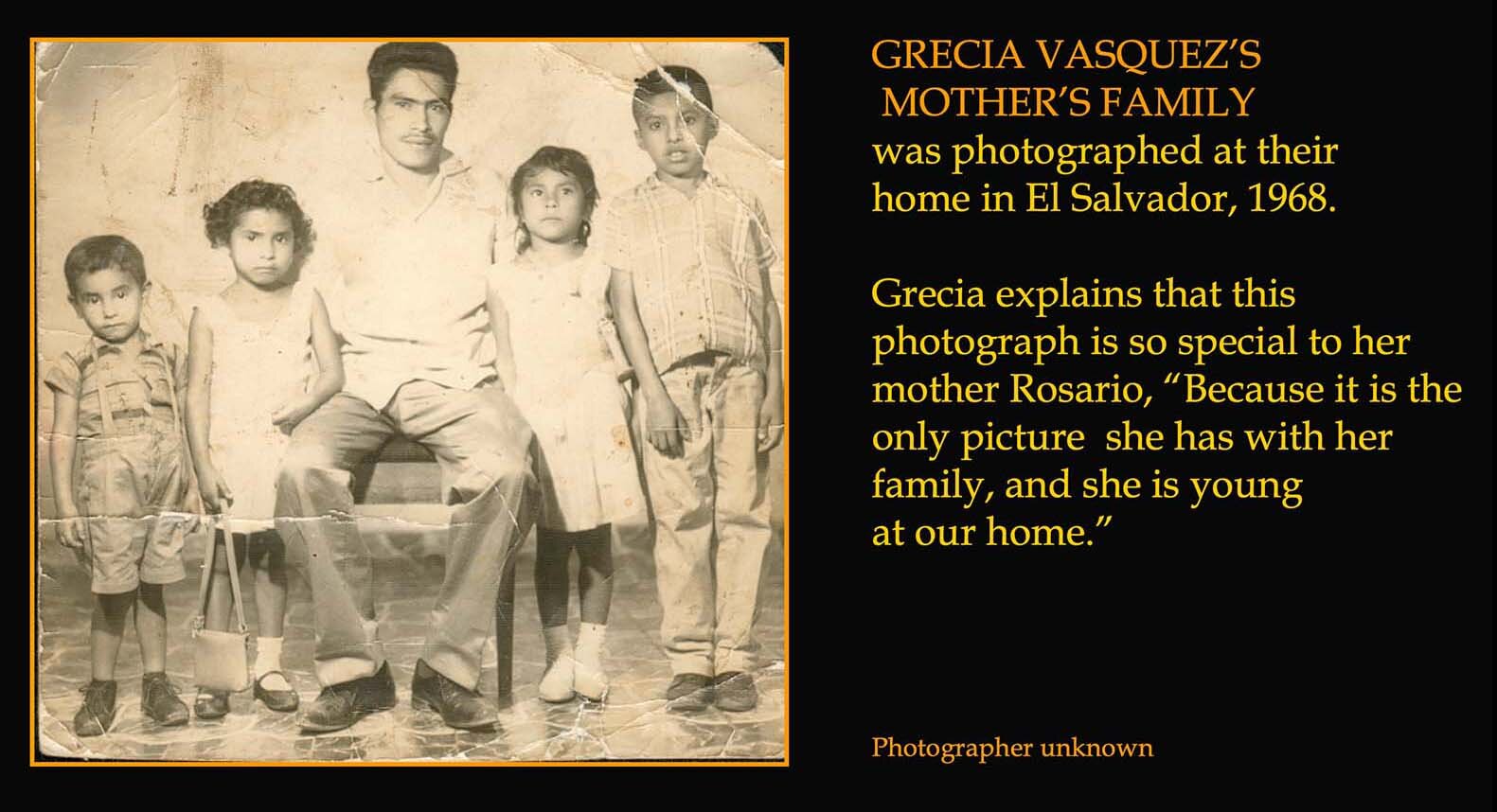

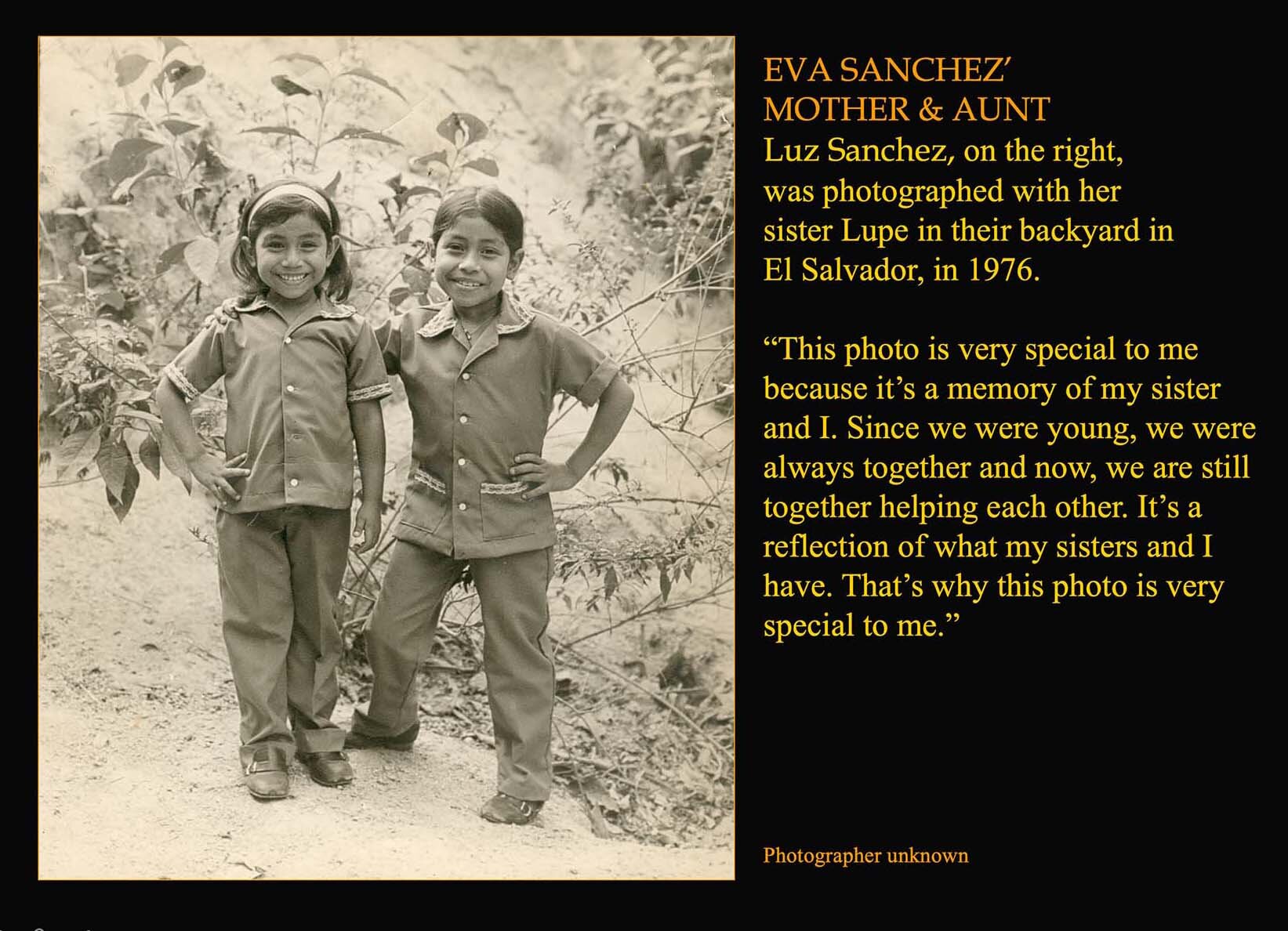

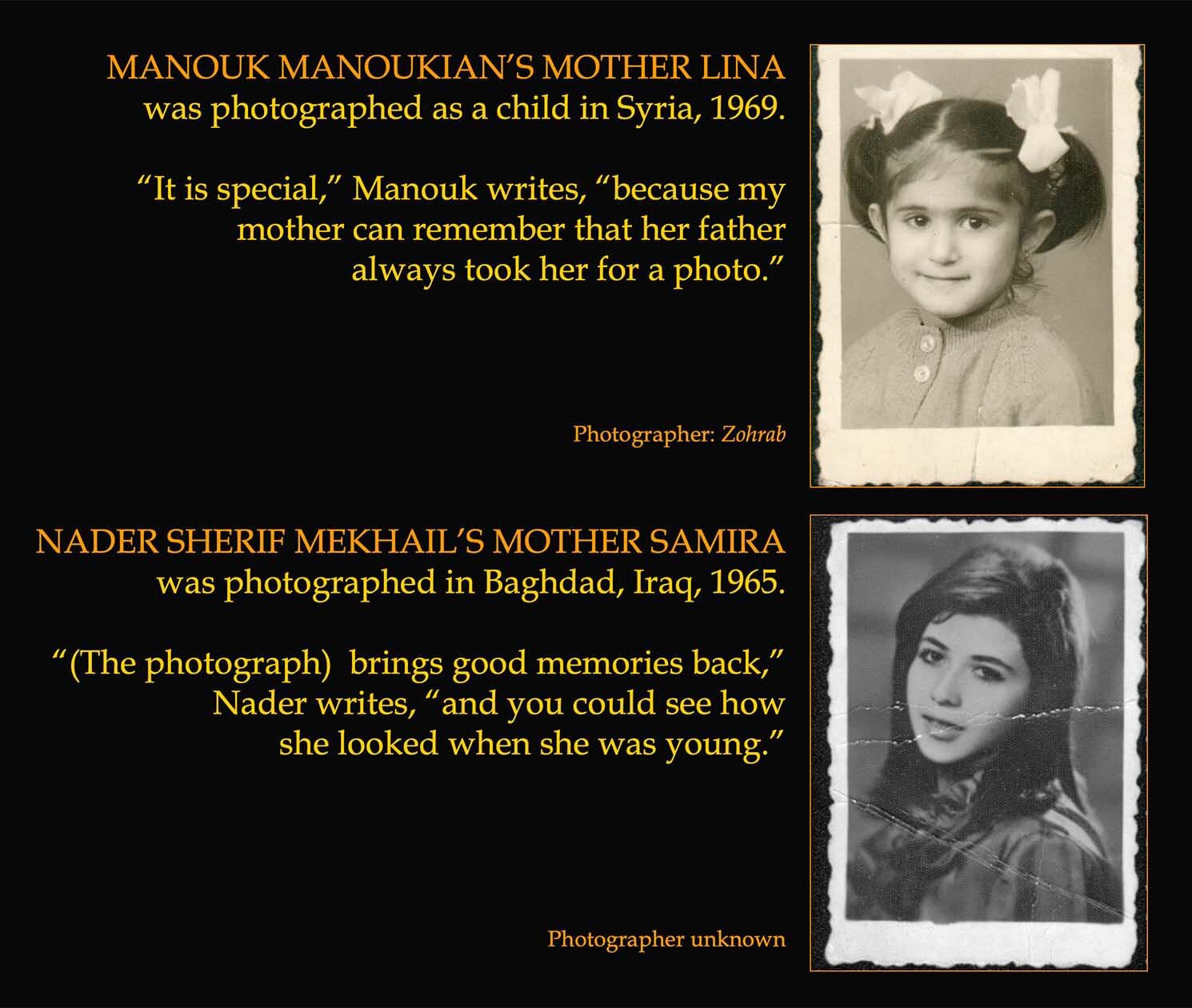

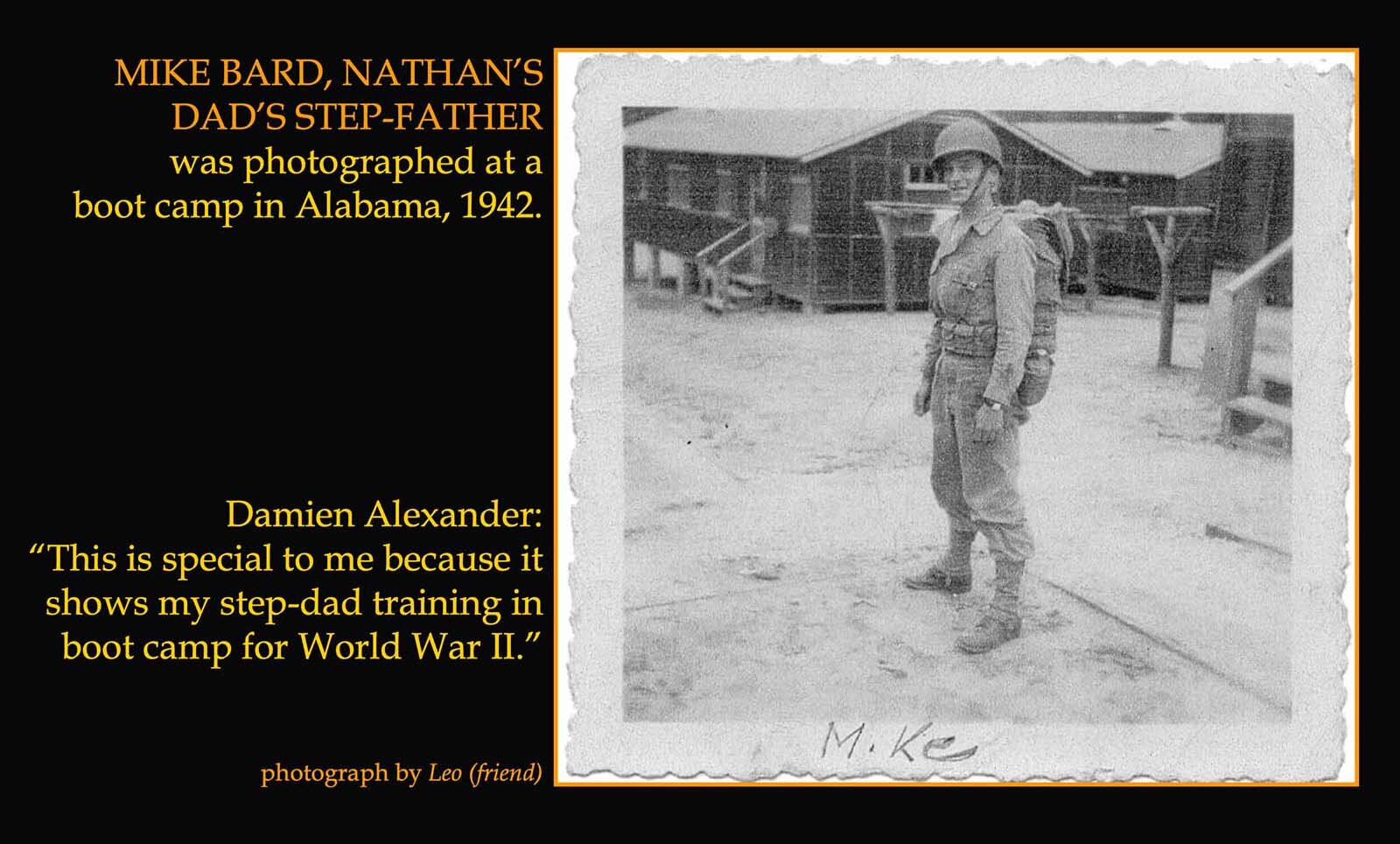

American-style materialist overkill notwithstanding, there is something enduring and humane about mimetic indulgence. During the course of this photography project, as I’ve sat in the living rooms and at the kitchen tables of my students, I’ve watched the faces of their parents as they proudly turned the pages of their own photo albums, happy to share their memories and show off their loved ones, some dearly missed, some gone forever. Whether looking at photos from El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, New York, Nairobi or Baghdad, there is a tone in the voice, some reaffirmation of a common humanity that emerges when people are sharing these images. (Fig. 3) Thus it could be said that although the photographs in this project, taken by myself and my students, contain punctum as unavoidably as they contain the elements of timing, lighting and composition organic in all photography, the attraction people have to their own family photographs cannot be explained by the punctum alone, with its reliance on the incidental. The use of any such academic theories or strictures would seem to diminish the sanctity with which these images are held.

Susan Sontag, in On Photography, sees it in a sociological light, directly related to the emergence of the nuclear family. As the industrialization of Western societies brought about the scattering of relatives, Sontag writes that this in turn has led to the deterioration of the extended family structure. Of the ten students participating in this project, nine of them belong to families that have within the last twenty years migrated to California from countries in Central America. All have left family members behind. The photos and videos made at the school assembly or wedding ceremony are sent to family members in far away places. The family photo album, Sontag rightly asserts, “is generally all about the extended family, and is often all that is left of it.” (9) Past generations, she reminds us, did without the luxury of ever knowing exactly what their ancestors looked like.

Something else Barthes wrote about punctum comes to mind. Aside from revealing form, punctumcan also be about intensity: Time and Death. According to Barthes, in photographs defined by their historical context, the punctum is death. "By giving me the absolute past of the pose," he wrote, "the photograph tells me death in the future . . . I shudder . . . over a catastrophe that has already happened." (Barthes 96) Sontag takes this line of thought a step further with her assertion that “all photographs are about death.” (11)

Could be. Death is something we all have in common. And so is Life. When a family sits for a portrait—whether it’s at JC Penney, or in their living room posing for their son and I-- they’re not giving much thought to how the image will be perceived when they are dead or dying. Photography, in this most democratic, universally used and accepted form, has always been about the seemingly simple creation of likenesses— the magical result of mixing Science and Art. The perceptions and interpretations that follow, colored as they are by perspectives that vary with age, gender, religion, politics, education, class and culture are useful academically. But these disciplines cannot be allowed to diminish the charm. To paraphrase Evans (who was referring to the aesthetics of documentary), the best photographs may not be art at all, but may be done in an artistic style. The answer to my query, I suspect, is yes. The “family photograph” must be the most democratic form of photography. The appreciation we show for these images are a direct reflection of the appreciation we show for the people in them, or those who show them to us. They bring us back to a grass-roots respect for humanity.

FORMATIVE THOUGHT PROCESSES

The die for this thesis project was cast long before I entered the graduate program in CSUN’s Art Department in 2000, before I gained the philosophic and critical understanding necessary to conduct the necessary research. And similarly, though I lacked the classroom experience needed to integrate an art-based, differentiated curriculum for gifted students, the preparation for this photography project began long before 1996, when I left a freelance career to become a public school teacher at Kittridge St. Elementary School in Van Nuys. I had been thinking and writing and teaching about the issues this project centers on— the photographer/subject relationship, the photograph as document/artwork, and the psychological and social impact photographs have on the cultures they depict-- since my days as an undergraduate student in the Journalism Department of this same university. However, it was not until my own photographic skills and ethics were truly put to the test, during my years in East Africa, that the seeds of a project of this nature were subconsciously planted.

I originally went to East Africa in January 1987, as Information Coordinator for a relief and development agency based in Camarillo, California. My responsibilities including visit regular visits to various field projects in countries such as Kenya, Uganda, Sudan and Zaire. I found the work exhilarating, as it allowed me to utilize the skills I had been developing while working toward my B.A.-- photography, writing, editing and design— while at the same time visiting incredibly obscure and dramatic places. After three very successful visits, I convinced headquarters that I should be allowed to move my fundraising operation to Nairobi (where I would be closer to both the action and the subjects of my steadily growing collection of portraits). After four years of running the Kenyan information office, I left the organization and started a new life from scratch, freelancing for various United Nations agencies, and other non-governmental organizations (NGO’s). I continued to travel widely throughout Africa, documenting life in refugee camps, street children, urban poor, and other topics. This soon led to my becoming a teacher of photography, for a wildly disparate set of student audiences. For Kodak, I traveled across Kenya, training groups of impoverished but hopeful jua kali photographers (those who made their meager living out in the hot sun on speculation, though it appeared that Kodak’s real concern was that these poor souls buy their product); for the All Africa Conference of Churches (Bishop Tutu’s affiliate in East Africa), I taught photojournalism courses for college-level participants from across the continent, while also creating a documentary exhibition on refugee life; for the Undugu Society of Kenya, an organization dedicated to helping street children and the urban poor, I began by taking photos for their public relations efforts, and eventually spent two years running their information department; for the government of the fledgling country of Eritrea, I spent a month in their capital city, running a photography workshop for former rebel soldiers being absorbed into the new order; and for the upscale French Cultural Centre in downtown Nairobi, I ran a series of black and white photography workshops for students of all backgrounds and class. Throughout it all I sought out portraits that I imagined captured the dignity and grace of the subjects, and I confess that I fell under the same spell as so many well-intentioned journalists, documentarians, and artists (if there need be separate categories here), of finding strikingly emotive photogenic qualities in the Otherness of the have-nots.

ON LIBERAL GUILT, SCOPOPHILIA, AND VOYEURISM

Scopophilia, epistemophilia, and the desire to master as ego instincts depend on social relations—I look at some object or that object looks at me—and produces narratives—my looking, knowing, and mastering suggest a development of my ego.”

* Paula Rabinowitz, They Must Be Represented: The Politics of Documentary

Paula Rabinowitz revives the age-old discussion about the interrelationship between looking and power (re: voyeurism and class consciousness), claiming that this has implications for “radical intellectuals” who “inhabit yet challenge bourgeois culture.” (Rabinowitz 35) Her arguments, (which are expressed from a boldly feminist point of view), raise the notion that photography, by its nature, distinguishes the observed from the observer, yet brings the two into contact. This, she asserts, “mirrors the troubling relationship of the leftist intellectual and her objects of knowledge—often cultures and classes different from her own.” (36) The result of this enterprise, which Rabinowitz links to Freud’s theories on Scopophilia (the pleasure of looking) and epistemophilia (the pleasure of knowing), are mimetic or literary images that “are produced by and produce the ‘political consciousness’ of middle-class culture.” (38) Rabinowitz chooses as a prime example Walker Evans and James Agee’s 1930’s classic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which attempted to depict with the greatest amount of detail and empathy the lives of dirt-poor southern sharecroppers (Figures 6.7):

Photograph by Walker Evans

“Agee’s ‘printed words’ and Evan’s ‘motionless camera’ produce the power of the gaze as a sexual and class practice. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men links the construction of the gaze — as a relationship of bourgeois subject to its object—and the mobilization of class consciousness—as the resistance of the reified object to its history.” (36)

This line of thinking is consistent with Sontag’s view that all photography is essentially a voyeuristic enterprise, an inherently aggressive medium that has always been “fascinated by social heights and lower depths.” (55)

Rabinowitz reaches the conclusion that “Voyeurism and its attendant sadism are at the heart of the documentary narrative.” (51) Once again, as with Barthe’s punctum, such intellectual analysis is necessary for the broadest academic purview, but is essentially overstated for the general population, especially the (so-called proletariat) working class, to which my students and their families belong. Imagine the pointlessness of trying to explain these theories to a group of people so enthusiastically and apparently innocently engaged in this photographic project, purely for the sake of their understanding and love for family and community. In this sense I see the role of photographer, and even photography teacher (as I have acted the role) not as voyeur, scopophile, artist, or even “subjective reporter” (whatever that contradiction may mean), however naturally all these comparisons and analogies may be applied. If anything, this type of work, because of all the intellectual supposition it creates, requires a postmodern apology, of the type provided by Agee:

“All of this, I repeat, seems to me curious, obscene, terrifying, and unfathomably mysterious. So does the whole course, in all its detail, of the effort of these persons to find, and to defend, what they sought: and the nature of their relationship with those with whom . . . they came into contact; and the subtlety, importance, and almost intangibility of the insights or revelations or oblique suggestions which under difference circumstances could never have materialized; so does the method of research which was partly evolved by them, partly forced upon them; so does the strange quality of relationship with those whose lives they so tenderly and sternly respected.” (Agee 8)

Slumming? Faced in Africa with the question of Liberal Guilt, I may have been in denial, and may still be so today, with regard to the current subject of my camera’s searching eye (the interiors of my students’ homes). After all, from amongst the ranks of the traditionally-minded educator, I have more than occasionally detected a distinct whiff of patronage toward our predominantly “minority” school community, of the kind so commonly found in the historical (and decidedly Eurocentric) colonial mentality. In response to this, in nearly every situation –- regardless of whether their level of material comfort was more or less than my own -- I have felt more empathy toward the subjects of my photographs than I have to fellow expatriates, colleagues or employers. This has not been an overt political stance on my part as much as a desire to belong, and an opportunity and impulse to create and express. A response to the curious conservative question “If not liberal guilt, why protest so loudly?” burns in postmodern futility throughout the pages Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which epitomized the enormity, complexity, and perhaps impossibility of creating a truly “honest” piece of journalism, documentary, or art.

EDUCATION AND PHOTOGRAPHY: A BRIEF HISTORY

“It is real sun painting, or rather it has been painted by me with pencils of light about ninety-three millions of miles long!”

* Oscar C. Rejlander, 1863

In 2000, as part of this graduate program, I taught an after-school photography class at a middle school in San Fernando. In an adjacent room, a painting class was being taught at the same time. As I was about to start the first lesson, a boy walked in and asked one of his friends why he was taking photography instead of “the art class.” Intending no disrespect to photography, his comment was nonetheless indicative of our society’s perception — even from childhood -- of photography as something that in top form may reach museum walls and attain the status of Art, but is more frequently thought of as a craft or vocation. This perception is well deserved, as photography’s utilitarian uses, including those employed in classrooms, far outnumber its usefulness as an art form. In this section, I will touch on the many historical, theoretical, technological and sociological factors that define this conclusion, and were considered in the making of this thesis project.

Photography emerged in a century during which history and temporality collided in the realm of expression, forcing western culture to encounter its presence as “historically specific.” (Druckrey 4) It also emerged in the era of the Romantic Paradigm, where its basis in science created an uproar in the sacred world of Art. Criticism of the new medium, such as this 1859 quote from Frenchman Charles Baudelaire, expressed the mid-18th century’s growing discomfort with machines, and took particular aim at the manner in which the camera’s mechanical process and exact replication of nature would diminish the high art of painting:

“As the photographic industry was the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies, this universal infatuation bore not only the mark of a blindness, an imbecility, but also had the air of a vengeance.” (Baudelaire 124)

Considered neither pure science nor art, photography’s true duty, Baudelaire contended, was as a “servant of the sciences and arts — but the very humble servant, like printing or shorthand.” (125) It is one of the medium’s great ironies that Walker Evans, who came as close as anyone to raising photography into the realm of High Art, cited Baudelaire’s “spiritual influence” on him. He considered Baudelaire, who had made urgent engagement with modern life the calling of the modern artist, the “father of modern literature.” Before picking up on photography, Evans had translated some of Baudelaire’s prose into English during a stay in Paris in the 1920’s, where he had gone to escape from the materialism of American life. (Evans 360)

THE RUSKIN FACTOR

“A square inch of a man’s engraving is worth all the photographs that were ever dipped in acid . . . photography can do against line engraving just what Madame Tussaud’s waxwork can do against sculpture.”

* John Ruskin, 1865

The question of photography’s scientific nature led to debate within the world of Art Education. Romanticist John Ruskin, the foremost English social and art critic, and a major influence on Art Education during photography’s infancy used his considerable weight to retard photography’s growth and acceptance. Ruskin had initially embraced the medium as a “great aid to art,” and in fact claimed to have been the first person to photograph the Matterhorn. (Goldberg PiP) Perhaps under siege by fellow Romantics, Ruskin soon changed his tune, deciding that photography used “neither the soul nor the active, designing intellect, and therefore could not be judged as a high art.” (PiP 152) To Ruskin, who believed that it was the intuitive power of artists that enabled them to discern the truths and beauties of nature, a mere photograph could not call upon “laws of organic form derived from nature as created by God.” (Efland 134-35) In 1879, he explained why he and others viewed photography as too perfect to be art:

“You may think that a bird’s nest by William Hunt is better than a real bird’s nest . . . But it would be better for us that all the pictures in the world perished, than that birds should cease to build nests. And it is precisely in its expression of this inferiority that the drawing itself becomes valuable. It is because a photograph cannot condemn itself that it is worthless. (emphasis mine) The glory of a great picture is in its shame; and the charm of it in expressing the pleasure of a loving heart that there is something better than picture.” (Ruskin 153)

One can imagine the reverberations this statement sent through Ruskin’s disciples at Oxford. Suffice to say, it would be a long time before England would see its first Art Photography curriculum.

LEWIS HINE’S TRUTH

“The documentary tradition in photography is an expression of the deepest moral and artistic values of liberal democratic societies. Both in celebration and protest, it is photography which has carried the evaluative burden which high art had abandoned, and it has paid the price.”

* Roger Seamon, “The Plight of Photography as a Modern Art, 1997

“In the last analysis, good photography is a question of art . . . Not art for it’s own sake, but art as a heightened awareness of the world.”

* Lewis Hine

In the United States, photography faced an equally difficult struggle for acceptance in educational arenas. The first university department to teach photography as a profession was finally established in San Francisco in 1946 by Ansel Adams, the renowned master of purist photography. Considering that Daguerre and Fox fixed photographic images into permanence back in the 1830s, this is emblematic of the low esteem in which Art Educators held photography.

Interestingly, the first union of photography and education resulted not from blessings bestowed by the Guardians of High Art, (who at the time were led by Alfred Stieglitz and his Photo Secession pictorialists), but rather from the social-realism world of documentary. The turn of the century was marked by a surge of realism, even critical realism. Muckraking journalists such as Ida Tarbell and Lincoln Steffens were in their primes. Jacob Riis, the Danish-born police reporter turned documentarist, exposed the deplorable living conditions of New York’s tenement slums with his groundbreaking book, How the Other Half Lives. (Figure 8) The Eight, a group of painters known as the Ashcan School because of their interest in revealing the underside of alley life, would have their first exhibition in 1908. (Goldberg)

In 1903, Lewis Hine, an idealistic young educator at the Ethical Culture School in New York, created the first full-scale photography education program. He felt that the educational value of photography fit neatly into the goals and methods of the “progressive education movement,” which the ECS curriculum promoted. The camera, he wrote, aided learning by sharpening perception. In the process of photographing the Ellis Island immigrants, Hine would eventually become famous for his pioneering documentary of child labor. Along with his mentor, Frank Manny, they sought out social issues to present their students with a larger worldview. (Trachtenberg 242)

While stressing the practical value of the camera and its importance as a tool for social change, Hine did not ignore the role of art in photography. Art appreciation, he argued, could be enhanced with photography. “In the last analysis, good photography is a question of art,” Hine told his students. “Not art for it’s own sake, but art as a heightened awareness of the world.” (242) Photo historian Alan Trachtenberg’s 1977 essay on Hine explained how the Hine bridged the gap between social documentary and “straight” photography, which was eclipsing Pictorialism as the en vogue genre in art photography:

“ For Hine, the art of photography lay in its ability to interpret the everyday world, that of work, of poverty, of factory, of street, household. He did not mean “beauty” or `personal expression.’ He meant how people live. A straight photographer, anticipating the direction of Strand and Stieglitz fter the demise of soft-focus romanticism, for Hine to be `straight’ meant more than the purity of photographic means; it meant also a responsibility to the truth of his vision.” (240)

Hine’s child labor images are characterized by casual compositions. One senses the easy rapport he seems to have struck with his child subjects. Having photographed war orphans and street children, I recognize similar expressions and body language-- indications of lost innocence and world-weariness, as circumstances force these young people to mature before their time. (Figs. 9,10)

Hine’s influence as an educator was fairly significant, even though his ability to transfer his commitment and passion to his students was likely limited to those who were sympathetic to his socialization of the craft. Paul Strand, considered by many to be among the top photographers of the last century, was a student at Ethical Culture. From Hine, Strand learned the fundamentals of camera and darkroom work, and how to use the open-flash pan of magnesium powder for indoor photography. And despite Hine’s overt dismissal of the studio-bound Photo-Secession stylists-- “From their ivory tower, how could they see way down to the substrata of it all?”-- he would take his students to Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery on Fifth Avenue. (292) It was here that Strand and the others were exposed to the work of David Octavious Hill, Julia Margaret Cameron, Clarence White, and Stieglitz. (Tomkins 17) Strand would consequently become a Photo-Secession regular. His finest work demonstrates the best of both worlds—technical artistry and emotive social import. (Figure 11) Another notable student of Lewis Hine was Roy Stryker, who would become the head of the FSA photographers during the Depression years. Stryker relied heavily on Hine’s wisdom (and stock photo archive), in the early years of his government career.

Today there are thousands of photography schools and university programs in this country alone. However, many of these institutions, such as the one this paper is being written for, offer no graduate level courses in photography, in neither the Art nor Journalism departments. Even so, one could argue that photography does not need institutionalized education to produce expert practitioners. There are plenty of excellent “how-to” books available, and once one is given the introductory lessons in camera operation, chemistry mixing, printing and developing technique, the natural artist will soon find his vision. Many of the most famous photographers in history were self-taught, or picked it up from friends and colleagues. Walker Evans, whose impossibly high standards forced him to abandon his literary aspirations and turn to photography in 1929, was essentially self-taught. Still, there is an element of cultivation and an aura of legitimacy in the educational arena. Evans spent his final years, until his death in 1975, teaching at the Art Department at Yale. Colleagues felt this afforded him a level of recognition and prestige that had been lacking in his career. (Pakay)

FROM KODAK TO DIGITAL: PHOTOGRAPHY FOR ALL

“What unites Dada, Surrealism, Pop, television, and ultimately the computer image, is their underlying relationship to the photographic.”

* Timothy Druckrey, “From Dada to Digital: Montage in the Twentieth Century,” 1994 (6)

Though there is still tremendously artistic black and white film being exposed, developed and printed-- think of photojournalist Sebastio Salgado, or the morbid stylings of Joel-Peter Witkin -- the world is becoming increasingly digital. From major newspapers such as the Los Angeles Times, to the journalism departments of schools around the world, the black and white darkroom is quickly becoming an anachronism. Forsaking the red light and chemical smell of the darkroom, negatives are now scanned and images perfected to the most finite detail for publication. Fine artists are using high quality digital printers to produce gallery quality prints. None of this should discourage the journalism and art departments from continuing to teach an appreciation for film, and fine handmade prints.

Digitalization, while pulling photography further from its “long-comforting narratives of nature and culture,” therefore serves to further diminish the medium’s original state and craft. (Figure 12) (Druckrey 4) An obverse analogy might be the effect that Kodak’s No. 1 camera had on the direction of photography in 1888. For the first time, the user could receive a loaded camera, make his 100 exposures, and ship the camera in for processing. “You press the button, we do the rest” was the slogan. This made it not only unnecessary, but also impossible for the photographers to process their own film and make their own prints. While photo historians may celebrate this as a triumph of technology and expediency, photo-historian A.D. Coleman sees it as a major setback:

“Up until 1888, anyone who wanted to make photographs had to practice photography. At a time when a growing public was acquiring craft expertise in the first democratically accessible visual communications system . . . Kodak, by appealing to people’s capacity for laziness—allowed the `luxury’ of foregoing any study of that craft. Eastman’s system effectively undermined the impulse to learn the process of photography, by rendering the knowledge unnecessary.” (Coleman 83)

The resultant alienation of the photographer from the full creative process is largely responsible for the common perception of the medium as a simple or automatic procedure. After all, it’s not inconceivable that a chimpanzee could make an interesting exposure or two out of roll of Tri-X, as long as he didn’t have to develop the film or print the images himself! Add human intelligence to the quotient and you still have the potential for image creation without much thought or effort. The purchaser of the Kodak No. 1, Sontag writes, could aim for a 100% success rate:

“ . . . guaranteed that the picture would be `without any mistake.’ In the fairy tale of photography the magic box insures veracity and banishes error, compensates for inexperience and rewards innocence.” (Sontag 53)

This would seem to make photography the perfect medium for students of elementary and middle school age. Indeed, handing students digital cameras, or point-and-shoot disposable cameras with color film -- the modern day equivalent of the old Kodaks-- implies that after some perfunctory lessons in composition and lighting, they are photographers, ready to add to the family photo album, or make artistic renderings of the geometry of street signs. Choosing film over digital for this project reflects my own preferences, and the far higher comfort level I have with film. Just as importantly, the choice to use film was predicated largely on expense: it’s not yet possible to find $20 digital cameras.

PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE CLASSROOM

“I don’t think very much about (composition) consciously, but I’m very aware of it unconsciously, instinctively. Deliberately discard it every once in a while not to be artistic. Composition is a schoolteacher’s word. Any artist composes.”

* Walker Evans

“Unlike other art forms, photography is one that allows the novice to produce interesting and satisfying images without hours and hours of formal instruction.”

*From Cross Cultural Images: The ETSU/NAU Special Photography Project, 1999

Today it is still rare to find fully-fledged art photography programs in elementary or middle schools. Interestingly, during a data base research on “photography in education,” most of the examples I found were neither art nor documentary. Rather, they outlined the various uses teachers, speech pathologists, and other educators have found for photography.

Photography, educator Michael P. Savage writes, is “a medium that is partly a language, but which resonates with thoughts, feelings and creativity that goes beyond verbalization.” (Savage 27) In his project, second graders were given inexpensive cameras, and asked to take twelve pictures of various people and places at school. These photos were then used to write stories. Children were able to “express their feelings through a new medium.” (27) Without wishing to appear cynical, this is a statement that begs questioning. The children were doubtlessly enthralled with their cameras the first time they were allowed to use them in school. But the medium will no longer be “new” the next time. Once the novelty wears off, will the results be the same, or will the children already be bored with it? Perhaps it’s a once-a-year project. The author did not elaborate. To avoid this potential pitfall, for my Kittridge students (who started using cameras while in fourth grade) the activities were not only designed to keep them engaged with issues relevant to their lives: family, friends, and community, they were often inspired by the interests of the students and their parents themselves.Incorporating social studies and photography history, and by having each student choose a famous photographer to research and write a biography on, ensured that the subject of “photography” would not be viewed as some optional extracurricular activity.

When teaching real camera work and beginning photography to young children, the mathematical -- aperture size, shutter and film speeds, developing times and temperatures-- and scientific --chemistry, properties of light-- aspects invariably make it difficult for them to concentrate on and appreciate the purely aesthetic elements. In my experience, children accustomed to instant gratification will initially resist the labor-intensive processes of black and white darkroom photography. Only when that first print appears under the red-filtered light, are new converts born. In the project at hand, the Kittridge students began with inexpensive (though not disposable) automatic cameras, shooting color film that was processed in a lab. For the later stages of the project, which brought into use a medium format camera and black and white film, I handled the darkroom tasks myself, as we lacked the facilities to put together our own darkroom at the school.

Most youth-oriented photography programs (outside of schools) are designed along the lines of social documentary, reflecting Hine’s belief that one can apply the most artistic principles in a meaningful context. Shooting Back, an organization founded in 1989 by photojournalist Jim Hubbard, put cameras in the hands of at-risk and homeless children on Indian reservations and in inner cities around the country. One of the stated aims of this project was “consciousness raising.” (Shooting Back 38) In the mid-nineties, the J. Paul Getty Trust funded Picture L.A.: Landmarks of a New Generation, a project that enlisted teen-agers from all around the city to document their communities. The workshops I ran at the Watts Towers Arts Center in South Central Los Angeles were assisted and inspired by both of those programs. (Figure 13) Whether the results can or should be called art is secondary. “The most important photography,” A.D. Coleman reminds us, “is emphatically not art.” (Coleman 481)

Some historical perspective: In the article “Photography and Art Education,” published in the November 1944 edition of School Arts, Lenore Grubert called photography “Perhaps one of the most prevalent interests that can be used by art teachers.” (Grubert 79) She recounts the story of Edward, who couldn’t stand art because he was terrible at it. Then one fine day the teacher discovered that Edward was a “camera enthusiast.” Before long, the boy was bringing in enlargements he had made in the science laboratory. Other students started using his “fine pictorial designs” to detect elementary compositional principles “as applied to photography.” Edward started toying with abstractions, and his growth as a photographer, the author declared, led him to the awareness “that compositions could be appreciated from a design viewpoint without the necessity of realistic interpretations.” (79)

This example is worth examining for two reasons. First, the enlargements were made in the science lab, not the art department. Should we be surprised that as late as the 1940’s, photography darkrooms were still situated in science departments? If so, we could also wonder why CSUN’s Art Department photo lab is in the science department today. Shades of Baudelaire, who believed photography’s true duty was that of servant to the sciences and arts. Defenders of the medium, such as Strand, view the relationship of art and science more like an arranged marriage. In 1917 Strand, to whom photography’s uniqueness lay in its “unqualified objectivity,” argued that good photographers, cognizant of the medium’s inherent qualities, had nothing to be ashamed of:

“Photography is the first and only important contribution, thus far, of science to the arts. Other arts are really anti-photographic.” (Strand 45)

The other noteworthy aspect of the 1944 example is the author’s characterization of Edward’s work as “fine pictorial designs,” useful for the “detection of compositional principles.” Despite the fact that this was during the heyday of social realism, Grubert either chose to ignore, or did not see the place in Art for the realism inherent in camera work. Rather than using photography as an end in itself, she encouraged her students to use it as Baudelaire’s “servant” to the arts. This mentality harkens back to the nineteenth century, when painters like Oscar G. Rejlander learned photography to assist in preparation for their paintings, then became obsessed with the medium and usually ended up becoming better known for their photography than their painting. Even though Rejlander’s combination print “Two Ways of Life,” an allegory on vice and virtue, was purchased by Queen Victoria, he never reconciled himself to photography being the “work of man.” (Figure 14) In 1863 he penned a guilt-inspired denial, “An Apology for Art-Photography,” in which he referred to photography as “a handmaid to art.” (Rejlander 142)

Today, photography is commonly used as an instructional aid in a variety of educational settings, including Special Education situations. There are several excellent case studies. In the February 1982 School Arts magazine, Paul Nash writes about the “Polaroid Education Project” which was started at his elementary school with the belief that “the creative use of photography in the classroom improves the students’ perceptual capacities and facilitates the development of a synthesis of image concept.” (Nash 35) Students made Polaroid snapshots of each other, then turned these photos into finger puppets, which reportedly helped those with speech problems speak more freely and articulately. The author’s conclusion that “the work of the project has proved that creative development of visual sensitivity actively enhances the capacity for cognitive, verbal, expression” is consistent with other examples I came across. (35) Speech Pathologist Nancy J. Tarulli has used photography for several years. She believes that “the application of photography into the speech-language pathologist’s collaboration, consultation and service delivery are limitless.” (Tarulli 55) In Tarulli’s experience, photography works because the reality-based images “help focus the child’s language on what he or she knows best.” (56)

The teacher-student relationship also benefits from the use of photography, though Nash’s description of how this occurs might leave those (like myself) uncomfortable with “teacher-speak” a little queasy. In the “triangular dynamic” of teacher, student and photograph, the teacher and student have “a common datum to examine and discuss.” The student “owns” the photo, thus the teacher becomes the student in his attempt to learn what the student had in mind when taking the photograph. Consequently the teacher learns to “see the world through their students’ eyes as the students manifest their perceived worlds on film.” (36)

No discussion of education could be complete without touching upon the issue of self-esteem. The relative simplicity of the photography compared to other media makes it useful in this respect. Of his second-graders, Savage, unwittingly echoing Sontag, was pleased to announce: “With picture taking there are no mistakes. (emphasis mine) This was great for children’s’ self-esteem.” (Savage 27) As would be the successful tying of shoelaces, or the completion of toilet training, I imagine. Any accomplishment achieved with a minimum of angst or inconvenience supposedly boosts the “self-esteem” of our psychologically fragile youth. This is one subject in which I agree with Rousseau. In our eagerness to coddle and encourage, we risk losing the development of true confidence, born of resiliency and struggle. Children (if not humiliated by insensitivity) learn the invaluable life qualities of grace and humility through trial and error, a process that is seminal to photography.

With regard to special education students, the concept of self-esteem gains validity. In each of the articles I researched, self-esteem was mentioned as a key result. Cross Cultural Images, a project for “mildly handicapped” 7-11 year olds in Appalachia, and on a Navajo reservation, was created by five Ph.D. holders from East Tennessee State and Northern Arizona State universities. Their students were taught to photograph subject matter deemed “representative of (their) unique geographical settings and cultural heritage.” (Montgomery 168). Although the students “clearly acquired the knowledge and skills to do good work in photography,” and the students were referred to as “photographers or artists,” the most powerful project results “were related to student pride and self-esteem.” (166) The last word goes to Susan Sontag:

“To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge--- and therefore, like power.” (Sontag 4)

REFERENCES

Agee, James, and Walker Evans. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1941.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1981.

Baudelaire, Charles. “The Salon of 1859.” Photography in Print. Ed. Vicki

Goldberg. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 123-126.

Coleman, A.D.. Depth of Field. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press,

1998.

Druckrey, Timothy. “From Dada to Digital: Montage in the Twentieth Century.”

Aperture 136 (1994): 4-7.

Efland, Arthur D. A History of Art Education: Intellectual and Social Currents in

Teaching the Visual Arts. New York: Teachers College Press, 1990.

Evans, Walker. Interview with Leslie Katz. Photography in Print. Ed. Vicki

Goldberg. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 359-369.

Grubert, Lenore. “Photography in the Classroom.” School Arts, Nov. (1944)

79-80

Lamuniere, Michelle. You Look Beautiful Like That. Cambridge, Yale University Press, 2001.

Montgomery, Donna. “Cross Cultural Images: The ETSU/NAU Special

Photography Project.” U.S. Tennessee 1999-03-00 6p

Nash, Paul. “Instant Photography and Learning: the Polaroid Education Project.”

School Arts 81 (1982) 34-37.

Rabinowitz, Paula. They Must Be Represented: The Politics of Documentary. London: Verso, 1994.

Rejlander, Oscar. “An Apology for Art-Photography.” Photography in Print. Ed.

Vicki Goldberg. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 141-147.

Ruskin, John. “Various Writings 1845-1879.” Photography in Print: Writings From

1816 to the Present. Ed. Vicki Goldberg. New York. Simon and Schuster, 1981. 152-154.

Savage, Michael P. and Derek Holcomb. “Children, Cameras and Challenging

Projects.” Young Children 54 (1999) 27-29)

Seamon, Roger. “From The World is Beautiful to The Family of Man: The Plight

of Photography as a Modern Art.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 55:3 (1997): 245-251.

Shooting Back: A Technical Assistance Manual. National Endowment for the

Arts. n.p., n.d.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Doubleday, 1973.

Strand, Paul. Interview with Milton Brown, 1971. Photography In Print. Ed. Vicki

Goldberg. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 288-290.

Tarulli, Nancy J. “Using Photography to Enhance Language and Learning.”

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 29 (1998) 54-57.

Trachtenberg, Alan. Classic Essays on Photography. Ed. Alan Trachtenberg.

New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980.

- - -. “Lewis Hine: The ‘World of His Art.” Photography in Print. Ed. Vicki

Goldberg. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 238-253.

Walker Evans/America. Dir. Sedat Pakay. Hudson Film Works, 2000.