The Innocent Always Suffer: Crisis in South Sudan

(Originally published in Kenya's Daily Nation, December 27, 1988)

By David Blumenkrantz

BACKGROUND

This article was written after a visit to Juba, December 2-4, 1988, accompanying an emergency food relief airlift sponsored by the United Nations' World Food Program. It was written as an expression of sorrow for innocent victims: farmers and pastoralists, children and elderly, who had been forced to abandon their homelands and face a new life of deprivation and hunger. There's no way to soft-pedal the simultaneous devastation of floods, famine, locusts and civil war. Lastly and by necessity, the article was meant as a look at the food relief industry, and the effect that free relief has on its recipients.

When the crowned heads of Europe met in Berlin in 1884 to divide the continent, borders were drawn without regard for the compatibility of the various tribes and races. This unfortunate geographic oversight is cited as one root cause of civil strife across post- and neocolonial Africa. Sudan might be considered a particularly egregious example of this colonial miscalculation. From the outset of Sudan's independence from England in 1955, the country has been divided among cultural, ideological and religious lines. In simplest terms, the Arab/Muslim north, which controls the country out of the capital city Khartoum, has been attempting to dominate the diverse (predominantly Christian and animist) people of sub-Saharan Africa. The potential for Big Oil Money factors in heavily. Since 1983 has there been little peace in South Sudan. The rebel faction Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA), led by John Garang has been leading an escalating conflict against the central government.

There are a plethora of concerns resulting from the power struggle, not the least of which is security—basic things like food, water, shelter and personal freedom cannot be taken for granted, or even expected. For the people in the south, the war has brought the economy, particularly in the rural sector, to a standstill. Rebel activity has forced multitudes to leave their villages and farmlands (already vulnerable drought). Most migrate to Juba where it is estimated that some 90,000 people are crowded into camps for the displaced, and many more recent arrivals can be seen gathered under trees and shop awnings in town. The reality is that many are weak from hunger, some found lying prostrate in the oppressive heat; people of all ages suffer from hunger-related illnesses. Random surveys conducted in several of the supplemental feeding centers throughout the camps have indicated malnutrition rates as high as 15%. Children are affected exponentially-- several schools in Juba have had to cease functioning in order to house the refugees. Shelter is limited-- at one camp, there were as around 30 people sleeping per tent, with many still outdoors.

The forced abandonment of farms is causing a major food shortage in the Equatoria region. The usual harvests, which supply food for most of the southern region, are not there this year. There is very little and sometimes no food in the shops and marketplaces, bringing additional tension to both the residents of Juba and the displaced. Further aggravating the situation, all roads leading to Juba are blocked by "anti-personnel" landmines, which not only prevents people from returning to their homelands, but also has virtually halted-- without the escort of government troops and minesweepers-- the importation of food by road to the town. This is true for most of south Sudan-- the small town of Yei is currently home to 65,000 displaced peoples living in six camps. Several organizations are involved in providing emergency relief, but their job is severely hindered by the insecurity on the roads. Airlifts have become an expensive but necessary solution.

The gigantic Hercules C130 spins downward at an improbable angle toward sun-baked Juba, the largest town in south Sudan's Equatoria region, carrying a precious cargo-- 200 sacks of maize, courtesy of the United Nation's World Food Program (WFP). Coming to a halt on the sweltering tarmac, the plane is immediately surrounded by locally hired laborers who scramble on board to unload the 18 tons. You notice and wonder what the men kneeling under the open cargo door are doing, frantically scraping the ground with their hands. Then you realize-- this is Juba, a town caught in civil war, and these men are scrounging for loose grains of maize to carry home to their families. Scenes like this are common in Juba these days.

There are children on the sandy, bleached playground of Juba One School, but they are not students. School has been closed to make room for more incoming displaced from the rural areas. The children climb in and out of tents, swarming anxiously around their teen-age siblings who stir large oil drums full of maize porridge over smoky fires. Inside tents, the eldest and weakest can only lay prostrate-- mere skeletons.

On a tattered blanket, Veronica Foni sits spread-eagle, sorting through some curious-looking green and purple plants. In her 70's, Foni wears only an old cloth tied over one bony shoulder, revealing undernourished ribs and a shriveled breast. She explains to her visitor that the plant is called Jarigo, scavenged from underwater sources to be eaten with her family's minimal ration of the maize porridge. "We are eating this-- there is no other food," she complains without much emotion. It was eight or nine months ago, her son adds, that the entire population of their farming village Jebelado was destroyed by rebel activity. They walked the 24 miles to Juba, where they have been moved from one location to another, awaiting entry to one of the more "permanent" camps for the displaced. Holding her hand to her chest, then to her mouth, Foni begs for assistance: "There are no vitamins in the body."

War turns the self-sufficient into dependents-- the healthy turn sickly-- the have-little become the have-nothings. In rural Africa, where fragile economies are already at the mercy of the rains, the vulnerability to war and the swiftness with which one can lose all are alarmingly pronounced. Caught between a right and a wrong that most care little about save for their land, families by the thousands have been uprooted in southern Sudan, their villages burnt to the ground by indiscriminate pillaging and the righteous ideals of zealous leaders and their incited followers. Juba today is a way station for all of south Sudan-- at least those fortunate enough to make it there. Thousands have reportedly died during mass exoduses out of the Equatoria region, and still thousands more languish in paralyzed isolation in satellite towns like Yei and Torit.

Peacetime Juba, according to those who have lived there since before the war restarted in 1983, was a lively, scenic paradise of sorts, with its share of nightspots. It was an attraction to a wide variety of visitors from Uganda, Zaire, and Kenya, as well as a fairly large expatriate community of development workers. As recently as this past October there was hope that the town, its population of 200,000 already heavily burdened by an increasing displaced population, could remain immune to the more extreme effects of the war. But an escalation of violence made road travel to and from Juba impossible without army escort, a situation that deteriorated to the point where it was no longer even remotely safe for lorry drivers to deliver relief materials, let alone common amenities. By early November only a handful of expatriates had resisted evacuation.

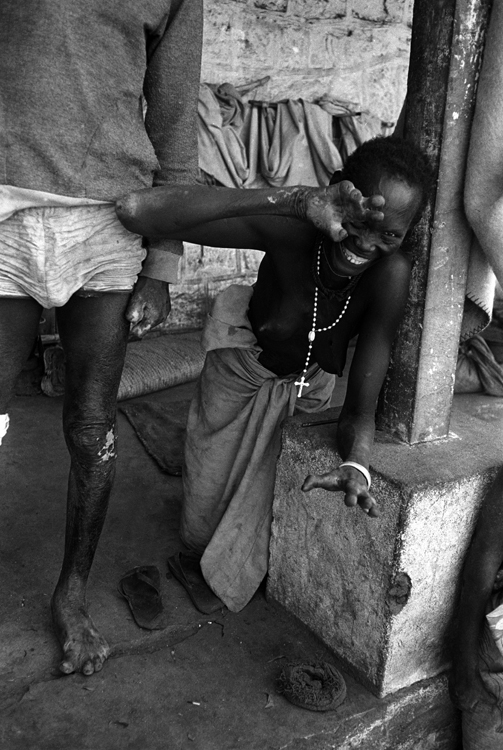

Wartime Juba features a different type of ethnic collage, crowding numerous camps for the displaced, inundating and forcing the closure of several schools, and turning downtown shop fronts into shelters for the lepers, who breastfeed babies with pronounced rib cages. They grind meager rations of grain and extend fingerless hands to shake those of a visitor. More recent newcomers cluster under trees, their worldly belongings in ragged tow while waiting for relocation. These are, among others, the Pojulu from the west; the Dinka from the north; the Kakwa from Yei; the Mundari, who were the first to arrive as displaced; the Kuku from the Uganda border; the Toposa from the Kenya border; and the Latuko from across the Nile, in and around Torit. These people number anywhere from 50-100,000. Once the owners of land and livestock, their passage home is blocked by anti-personnel landmines. An additional 65,000 are camped in Yei, and a similar number or perhaps more survive in Torit, according to estimates by relief agencies-- reportedly the situations there are even more desperate than Juba's.

A TOWN LACKING SUBSTANCE

Late afternoons in Juba's camps for the displaced are eerie. By 4:00, when the sun has reached well into its downward arc toward the horizon, the stifling heat of the dry season lets up just a notch, and the western sky appears an ominous hazy red-- a dusty warning that with each passing day, the desertification of northern Africa is creeping closer. There's a strange silence, as the heavy air mutes the high-pitched laugh or the whimper of a child, and the monotone conversations of men and women discussing survival. This falsely surreal tranquility is broken only by the occasional roar of a plane bringing relief food and supplies, (military maneuvers were quiet during my stay-- only one jet fighter took off), or the few lorries and four-wheel drive vehicles operated by government and non-governmental agencies, sputtering down dirt roads in and around the camps. Otherwise the singing of birds and the padding of barefoot children towing water and firewood home from the banks of the Nile and her tributaries usher the evening in. Evenings of little to eat, especially for those not displaced long enough to have taken advantage of the recently-ended rainy season to cultivate dura and a few other subsistence crops.

Many of the displaced are the farmers who traditionally provide food for Juba's markets. Hence this season, with the exception of "the intensification of agricultural development inside Juba," (according to a representative of Catholic Relief Services), there were no harvests-- the impact of which is being felt not only among the displaced population, but the town's residents as well. The evenings, warm enough to sleep without a blanket, reveal a Juba that seems half dead. Tea shops still do a reasonable business for the locals, a mixture of Arabic jellibia-clad northerners and the southern Nilotes. A quick look through fluorescent-lit shops presents a wealth of imported clothing, watches, shoes and other items, but in comparison to the little found in the markets, and the under-stocked chemists, that abundance seems a mocking paradox. When asked what would have transpired had there been no food airlifted, Francis, a young man who works as a housekeeper for one of the relief agencies, theorized that those who would be able to move out would try to do so, but those already "paralyzed" could only "remain and would have to die."

There is no question that the food airlifts, initiated by the World Food Program on October 26, have staved off what easily could have become a catastrophe. The airlifts were begun as a last resort in response to the increasing amount of ambushes and lootings on the roads leading to Juba. These roads are, especially during the rainy seasons, in virtually impassable condition already-- the 100 miles from Yei to Juba can take three days or more. For some, the airlifts were a welcome means of escape from the isolation and strangulation of Juba's siege mentality. The evacuation of personnel, and the free return to Entebbe of 22 lorries abandoned during the convoy violence that saw eight Kenyan drivers killed, continued until early December. Since late October, WFP's three flights per day from Entebbe alone have brought in nearly 3,000 tons of mostly maize and some beans. Other organizations and governments have also responded, and for several weeks airlifts have been arriving from Entebbe, Nairobi and Khartoum, bringing thousands of tons of foodstuffs, blankets, tents, utensils and medicines.

In most camps, where surveys indicate that malnutrition rates among children are as high as 15%, even a nominal amount of help is a boon. At Lologo, one of the largest camps (holding 24,000 people), residents crowd around huge lorries that bring, without warning, sacks of maize for the feeding centers. Dario Ochilo, a one-legged man on a crutch smiles broadly as he watches the sacks being tossed into piles. Ochilo, a former schoolteacher in Torit, tells how he and his 15 children were forced to flee Torit three years ago, because of the war. "They took all I had-- food, everything . . ." He explains that his wife died "years ago," and that the family had survived until now because the children "go to the bush to collect firewood to sell for food money." But since the roads were closed and the markets dried up, as another man put it, "it doesn't matter if you have money or not-- there's little to buy." Still, Ochilo is grateful for the food relief. "It's better now," he says optimistically. "The hunger."

The needs are overwhelming. Piolegge, a spokesman for people displaced from Kwarijik Luri, some seven miles away, wonders why more sacks of maize have not yet been delivered. "No feeding today, only for the children," he shrugs. He points to a canvas tent, built to hold perhaps six people. "The problem is shelter-- we have only eight tents for 1,000 people. We are sleeping 30 people to a tent, and the rest are still sleeping outside." Others complain that the food relief being allotted "is not enough" for their families, and that they are lacking essentials such as oil and beans.

STOMACHS HALF FULL OR HALF EMPTY?

To the outside observer, and certainly to the pessimist, the relief effort presents a myriad of problems-- a quagmire of logistical complaints, contradictory objectives and most importantly the unfulfilled expectations of the beneficiaries. This however, does not afford enough credit and respect to those involved on a daily basis in what is an extremely pressurized and complex situation. As a veteran of World Food Program in Nairobi lamented, "there are very few people who stay in the emergency relief business very long-- it is very hard work." Observing the frantic pace and long, demanding hours of those involved in today the above remark seems an understatement of sorts. Two logistics monitors of the WFP airlifts from Entebbe recently confided that they had put in six straight weeks of 8-10 hour days, without a break, and their man in Juba can say the same.

The problems crop up fast and furious, and seem to multiply. With little food available in the open market, the population of Juba grew restless while watching food donations from agencies such as USAID, EEC and CRS arrive with strings attached-- meaning that there were strict stipulations that the priority for distribution goes to the indigent, the displaced, the disabled, and the feeding centers. An estimated 50,000 Juba residents, declaring themselves to be as victimized by the war as the displaced, have posed as displaced in order to receive free food, resulting in a dilution of the impact the airlifted food has had in the camps. Others have joined demonstrations and threatened to open storage places by force. To quell the hungry masses, 180 tons of food was released to the ERCU (Equatoria Region Cooperative Union, a body established to fend for the interests of the working class), for distribution to the community at large. This food was later restocked for the displaced from a donation of 300 tons of maize from the government of Kenya. Other natural hindrances have arisen as well, such as the pilfering of some of the food from their burlap sacks, the delivery of spoiled food to the feeding centers, and uncertain allegations of opportunists taking advantage of the crisis for their personal gain.

Ed- It came to my attention during subsequent visits that food relief was commonly siphoned off to feed the soldiers of the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA), an allegation I could not verify independently, but which I heard from several sources.

In early December, these issues and several others were hammered out at a workshop held at the Nyakuron Cultural Center, a covered amphitheater that was once part of Juba's premier nightspots. The two-day event, convened to sort out the many falsehoods that have hindered the relief effort, as well as chart the plans for the upcoming months, provided a platform for group discussions and debate between the various bodies involved: the displaced, who were represented by their senior chiefs; the Juba residents, represented by the ERCU; and the eight non-governmental agencies currently involved in providing relief and operating feeding centers and other development programs such as women's support groups, medical and agricultural assistance in the camps. The workshop was sponsored by CART (Combined Relief Agencies Team), who coordinates the efforts of the various NGO's.

The Sudanese government, not immune to criticism, was represented by the governor of the Equatoria Region, Morris Lawiya. The stakes were high; it was a no-holds-barred workshop. As passersby would stop to peer in and listen through the chain link fence that surrounds the venue, speaker after speaker attempted to clear the air of misunderstandings that had accumulated up to that point. At the same time it was obvious that the participants were dedicated to finding the necessary solutions to help those in need-- both the officially displaced as well as the local community.

The urgency of ironing out the differences was underscored by a series of testimonies. The Paramount Chief of the displaced people, a wobbly-legged Arabic-speaking graybeard, made it clear in a speech that was authoritative, angry and imploring, that his people, suffering as they were, were "not satisfied with all the methods of relief being offered." Equally adamant was the speaker for the ECRU, who asked, "Who are the victims of war?" insisting that the aid should be extended to other victims who have also been affected by the floods and desertification. In light of the chaos that has engulfed the countryside, he claimed, "everyone's displaced, and everyone is affected by the war."

Egil Herdan, a Danish national working as a representative of WFP, has been organizing the airlifts from Entebbe. He stressed the unavoidable logistical problems inherent in emergency relief situations, and warned of the side effects of relief-- passiveness, dependence and a migration to relief areas. He expressed hope that all the parties involved would soon be able to turn their efforts to development rather than relief, "to teach people to earn rather than to give them bread."

Constructive criticisms and debates aside, several self-evident truths came forth in the workshop. It was agreed that relief efforts should continue for "as long as the war exists, and after the war a rehabilitation program should start." It was also made imperative that relief efforts be extended to the rural areas, and should include medicines, fish, beans, salt and other high-protein relief for malnourished children.

A representative of CRS, an eight-year veteran of Juba's ups and downs, outlined two possible scenarios: "If the war stops, the first thing will be to get the people out of the camps and back to their homelands. For the farmers, the first needs will be shelter, food, seeds and tools for agriculture. For pastoralists, who have lost their livestock, it's a more difficult question, as it's harder for them to resettle." Should the war not end quickly, "it will be a more desperate situation. Efforts to cultivate Juba will need to be increased, as will shelter so that the schools can resume." He cites an urgent need for boreholes, utensils and other relief supplies.

Although the officials in Juba, who are carrying the burden of this and the next generations, understand that the problems of Sudan's people are intertwined with political and economic decisions made in that country, they are grateful for the outpouring of concern from "our brothers throughout the world." When the war will end, nobody knows. Even as solutions to the web of problems were being discussed, it was reported that four more people were killed in an ambush on the road between Yei and Juba. In spite of the risks involved, WFP is planning, providing they can guarantee their drivers' protection, to resume relief convoys in mid-January, when the roads are drier. Partly to reduce the exorbitant airlift costs, and mainly to gain access to the besieged remote areas, the lorries should be able to help an "urgent need" that airplanes cannot reach.

Urgent need. Urgent need. Above the heads of destitute children oblivious to their fate, those words swirl with the dust of the encroaching desert. Elders look to those same skies for a sign of an end to their plight. For the tens of thousands of South Sudanese whose lives are being threatened by circumstances beyond their control, let's hope that airplanes full of food will not for long be their only salvation.