The Misfits: Life and Death in Ankoro

1987

We had a magnificent lightening storm last night, intermittent bursts of energy illuminating the entire horizon. Kisimba and I, along with a local friend of his called Angelina were in the living room of Dr. Steiner's brick Ankoro home. The doctor was napping after a full day of consultations and procedures. Raphael was in the small kitchen preparing an Italian dinner. There was a furtive knock on the door, and a harried looking middle-aged man dressed in ill-fitting, dirty clothing entered nervously. He spoke urgently in Kiluba to Kisimba who rushed in to wake the doctor. It was a woman at the hospital, an emergency. That was all I could tell, but I grabbed my camera gear, preparing to document Steiner in action at night.

But he didn't go. "The baby is already dead. Dr. Kabwe will take care of it."

We jumped in the Land Rover and picked up Dr. Kabwe, who was waiting in the dark rain along the road. "Good evening, how are you?" he asked with unforced calm. We hurried to the hospital, passing several people walking, pace unchanged by the weather. Kabwe was painfully composed. "You like the jungle?" He seemed surprised and amused that someone from California, a mythical place as he described it, could find the bush conditions so agreeable.

In a few minutes we pulled up at the hospital. As always there were several people around the building, mostly mothers with children sitting under the awning, quietly talking amongst themselves. We barged into the maternity room. My heart lodged in my throat. On a stark wooden table a middle-aged women was lying naked on her back, surrounded by a small group of attendants and nurses. She was in intense pain, moaning. Between her legs hung the blue-black head of her dead unborn child. Partially severed arms, white from blood drainage, hung limply. An ominous weight descend upon me as I numbly proceeded to snap off a few frames. This was to be one of those situations where I was glad to have the camera to work behind.

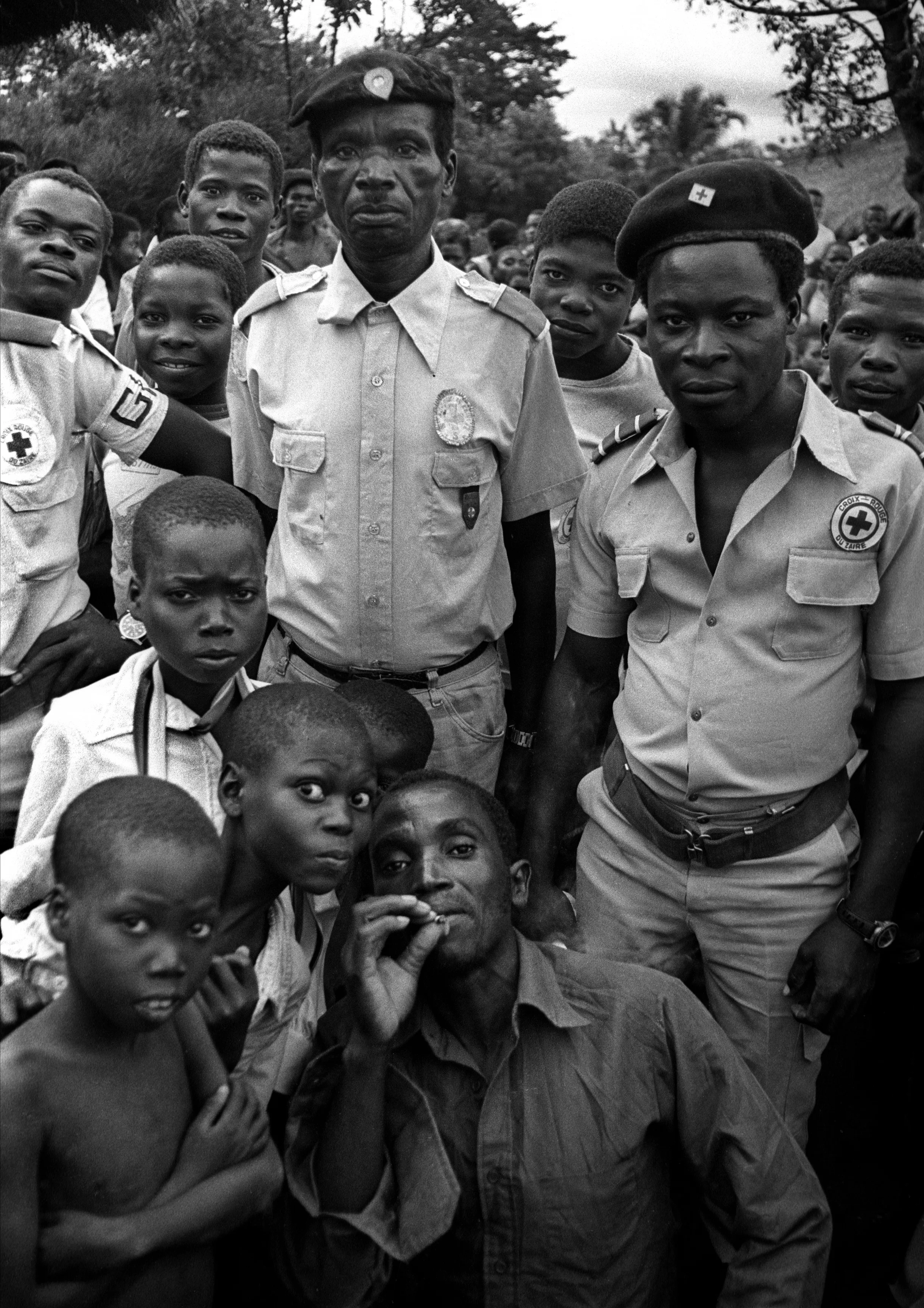

The woman, who had delivered twelve children in her life, lived in the village of Mukale, about twenty-five kilometers of bad road away. A "Red Cross Soldier,” the Zairian outfit which Dr. Steiner scoffed "know nothing about medicine, but have nice uniforms,” had attempted a botched delivery. The child was stillborn, and in an ill-conceived attempt to remove the body, he had cut away at the arms and umbilical chord, severely puncturing the uterus and causing vast internal bleeding. The woman had carried all the way to Ankoro on a makeshift stretcher, with the baby in its present condition.

Dr. Kabwe discussed the situation at length with his staff, hesitant to take action. In an adjacent bed, another women lay staring straight ahead with dull, yellow eyes. It was all too nonchalant for me. Kabwe at one point turned to me as I was taking photos, and in his deadpan English, explained, "Delivery is not easy. This is one of the problems of tropical medicine."

Outside the maternity room, the woman’s husband, had been fishing in another village when he was summoned, was pacing anxiously. He too was dressed in tattered clothing. Kisimba said he was foolish for not bringing her to the hospital earlier. He seemed disturbed; Kisimba thought he was deranged. He spoke angrily, growing more agitated as the hospital staff gathered round to listen.

Confounded, Kabwe at last decided to consult Dr. Steiner. We rushed back and found him enthusiastically eating his spaghetti dinner, and enjoying a bottle of Spanish wine. Apologizing for having started without me, his calm was strangely reassuring. He realized that what I had seen was "horrible, it's horrible," and explained that he didn't go at first because Kabwe, as the head doctor in Ankoro, had to learn to handle these things. I barely touched my dinner, but swallowed a few large glasses of the wine. Preparing to go to the hospital, Steiner explained in his best Swiss-German accent that Kabwe should have just reached in, and "popped zee baby out," but was "perhaps frightened."

Such are the vagaries of tropical medicine. People are hesitant to use hospitals, not only because of the distance I was told, but also out of ignorance. There are still the natural healers or medicine men who many people in the bush prefer to trust. As Dr. Steiner went to the hospital, I stayed at the house, thinking the emergency was over. He returned shortly, but the news was not good. While digging out the last of the baby he had inadvertently gone through the existing hole in the uterus, tearing some of the bowel cavity intestines. As a result, severe bleeding ensued. A nurse came to the door, and the doctor had to go back to operate. I went along to document the operation.

Scrub nurses in rubber beach sandals, wearing kitenge dresses under their smocks, prepared the instruments and table. In the hallway outside the operating room, two of the attendants pleaded with me to take their photograph. I was used to these requests, but at a time like this? I took one, and others wanted more. It became ridiculous, with the attendants walking with exaggerated importance down the hallway. They laughed hysterically and gave me the thumbs up sign as I snapped the shutter.

They brought the patient in on a stretcher, and laid her down in the hallway, while final preparations were hurriedly being made behind the double doors. More photo requests. "Kazi kubwa!" (Important work!) I insisted. They took this as a sign that I wanted them to pose working. They crowded around the suffering woman, pointing at her while pantomiming medical care. It was straight out of the Marx Brothers, except this woman was bleeding to death.

Into this madness came a shirtless Dr. Steiner. He ordered the staff into action. The patient was put on the table, anesthetized and attended to intravenously. As the doctor was helped on with his smock and gloves, the woman lay there, naked, her insides bleeding profusely, her bloated stomach glistening. From her half-parted lips came soft, resigned moaning.

At 9:30pm the stomach was cut open, a "midline incision," and the operation was underway. The generator, which normally brought electricity to the otherwise powerless village hospital from sundown until 10 each weekday, would stay on late this night. Steiner worked swiftly, deftly, frantically. Accepting no hesitations or mistakes from his staff, he pulled out the uterus, the remains of the child, and finally about two feet of small bowel intestines. It was a horrific site. "It is horrible, just horrible," Steiner had warned me as we entered the hospital. "Just horrible."

The patient's eyes were closing, rolling up in her head. Blood was filling the drainage bottles beside the operating table, which was surrounded by the two doctors and a half-dozen pairs of sandaled feet and the semi-sure hands of a homegrown staff of trainees. It was too grim for contemplation. My adrenaline was pumping as I photographed, and Steiner once warned me not to lean on the patient for risk of infection. He finally announced that the bleeding had stopped. The accomplished Swiss surgeon became increasingly impatient with fundamental mistakes. Brow furrowed permanently, he implored Kabwe in French, "Sil vous plait le docteurrrrr," drawing out the last syllable for emphasis. Indeed, Kabwe was a relative trainee, a fact not lost on either of them. This woman would likely have died had Steiner not been in Ankoro that night.

After more than 90 minutes, Steiner announced "It was a run for life for a while there." As he worked swiftly to close up the stomach, the atmosphere lightened up a bit. The staff all laughed when Steiner berated an assistant for cutting both sutures instead of just one, forcing him to start anew. Giddiness returned to the camera hams who were standing on footstools behind the doctor, monitoring an I.V. They started signaling again for me to take more photos. When I questioned Steiner about them the next morning he shrugged it off, explaining, "they do the job they have to do, but very few get personally involved with the patient."

When the last stitch was in, the doctor sat down in a small storeroom to fill out his report. I looked in on the patient. The operating room was a disaster, the floor covered with bloody cloths, cotton, wrappers and hoses. There were dozens of dirty tools. The patient lay alone under the bright operating lights, naked but for the bandage on her stomach, which convulsed irregularly, a sign of life.

This was my introduction to tropical medicine; this was the worst of the infamous Third World. Survival or a horrible, preventable death, dealt out by the hand of fate. A desperate effort to safe the life of one villager, provided by a non-governmental organization.

POSTSCRIPT

The next day, for the first time since I had arrived in Africa some one week earlier, I was overcome with sadness, shame and confusion. Such a harsh realization, that underneath the surface of a romantic notion, reality waits in the form of misfortune and injustice. I refused to accept the notion that people only cared if confronted with photographs of starving children with doe-like eyes.

I thought I had found out something that Dr. Andreas Steiner had known for a long time, back when he took over the stewardship of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Gabon. Every family I saw, crouched on crude porches or in front of small fires in some remote village, deserves the same care as the woman resting in the Ankoro Hospital.

“Who’s to blame?” I wrote in my journal with a furious resignation. “How about the medical assistants who bugged me for photographs? Not even Dr. Kabwe was prepared to handle yesterday's catastrophe. The only guilt I can sense right now is for humanity. For the Mobutu regime, certainly, but also for the non-humanitarian actions of global neighbors who continue on their paths toward enlightenment through the pursuit of wealth, while allowing situations like this to further deteriorate.”

There was a measure of justice. Dr. Kabwe, as the medical authority of the Ankoro Health Zone, was charged with arresting the incompetent Red Cross Soldier. The woman, I’m told, survived the ordeal. “Worse for the wear,” I scribbled, “she will live out her life with the same spirits lifting her as before.”

Outside my window in the sun-bleached and gorgeous environs, a lone boy walked down a humid, pristine path. For the remainder of that first two-week stay in Zaire the children still smiled and waved, and the adults continued to accord me as politely as ever. I was soon able to laugh with Kisimba and the others again, as we checked our cultural barriers at the door and enjoyed each other’s company, as young men do everywhere. I was so glad to find a friend there to intuit my intentions in such an accommodating manner.

Just days earlier in California, the director of our Christian-based NGO had sent me off on this first trip with a well-worn cliché. “There are three types of people that go to Africa: missionaries, mercenaries and misfits.” I had no idea then what he was talking about, but in my dealings with the few expatriates I have met in Zaire, find these generalizations too broad. Andreas Steiner seems the classic example of a duality in human nature that renders such categorizations moot. Widely considered, by his own description, to be something of a Great White Medicine Man throughout the Shaba Province where he oversees three hospitals and several smaller clinics, Steiner has been criticized by local Methodists for what they deem as his unexemplary lifestyle. Celia, his pretty young Zairean wife, realizes that her husband, who left a previous African wife behind in Gabon, enjoys his elevated status. On our first evening in Ankoro, sipping cold beer as the dusk slowly engulfed us he offered this rationalization. "When I am about to operate on a dying person, they do not ask me, 'How many women are you sleeping with?' I consider myself a Christian, but not a fanatic. What we are doing here you could probably call Christian. If a man drinks, or loves a woman, this is not so bad; it's what he does overall that counts." Whatever has drawn Steiner to this remote, self-contained existence, he manages to blend his better angels with his own self-interest.

My own presence here must bring into focus a variety of perceptions. I’m the starry-eyed newcomer, a soft touch for a favor, open to mischief. The NGO-sponsored philanthropist with the requisite reserve of compassion, curiosity and purpose, known to those with a more cynical sense of history as the invasive carrier of tools of exploitation in the service of an imperialistic lens culture. The children, when they are not fleeing the sight of me, consider me the friendly magician with gadgets dangling from his neck and shoulders. No matter how I’m perceived, it can be only vanity to measure my personal cathartic experiences against the collective African experience.