Street Children, the Offspring of Urban Poverty

Njoroge, perhaps ten years old, was being interviewed by social workers. His only possession was an old burlap sack. When asked why he wouldn't put the sack down as they talked, the boy replied warily, "This is not a sack. It is my father and my mother, my house, my car, my farm and my daily bread. I can't steal without it." He showed no embarrassment in his tattered sports coat, replete with missing arm, and though scrubbed in a drainage ditch at Uhuru Park, the stench of urine. His is a childlike mischievousness gone bad, a studied toughness born of fear. A future limited by injustices beyond his making, his only choice is to survive.

Nairobi, like other major towns and cities in Africa and elsewhere, suffers from urban blight. For decades, the flow of rural-to-urban migration has continued unabated, with thousands abandoning their pastoral or peasant farming existences for the lure and promise of city life. Many end up unemployed and disillusioned. Thus for a large percentage of Nairobi's 3 million inhabitants, life is a day-to-day struggle. Nearly half the people live in sprawling slum settlements on the city's periphery, where clean water, sanitation, nutrition and security are rare commodities. Spawned from these squalid conditions are the street children, forced by circumstance to take to the streets for survival. Worldwide, UNICEF estimates there are 100 million such children, living by their wits in the alleyways and on the avenues of cities such as Sao Paulo, Calcutta and Mexico City.

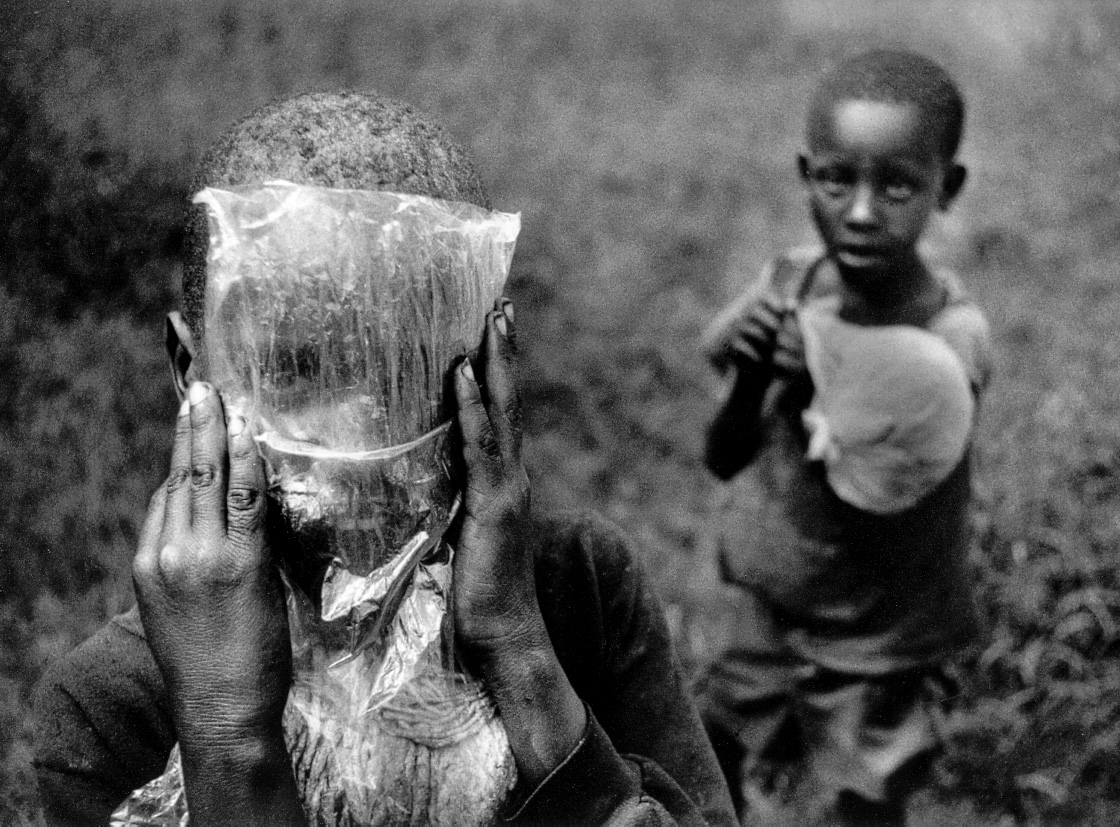

In Nairobi alone, the estimated number varies wildly, from 60,000 to more than 100,000. It is a sad paradox of modern life, the sight of neglected children roaming the streets, searching for food in dustbins, harassing pedestrians and motorists, sleeping on the street, or inside cardboard and polythene structures. The more industrious collect scrap paper to sell to recyclers, or become "parking boys," guiding cars in and out of parking spots in the city center for a few coins. Girls are particularly susceptible to child prostitution, leading to psychological degradation, veneral diseases and AIDS. There is a constant fear of police harassment; the children are beaten and frequently swept off the streets and locked up in dehumanizing conditions, either in remand homes or jail cells. Eventually they are released back onto the streets, hungrier, angrier, and more desperate than ever. The brain-deadening high of industrial glue sniffing is an affordable escape from these realities.

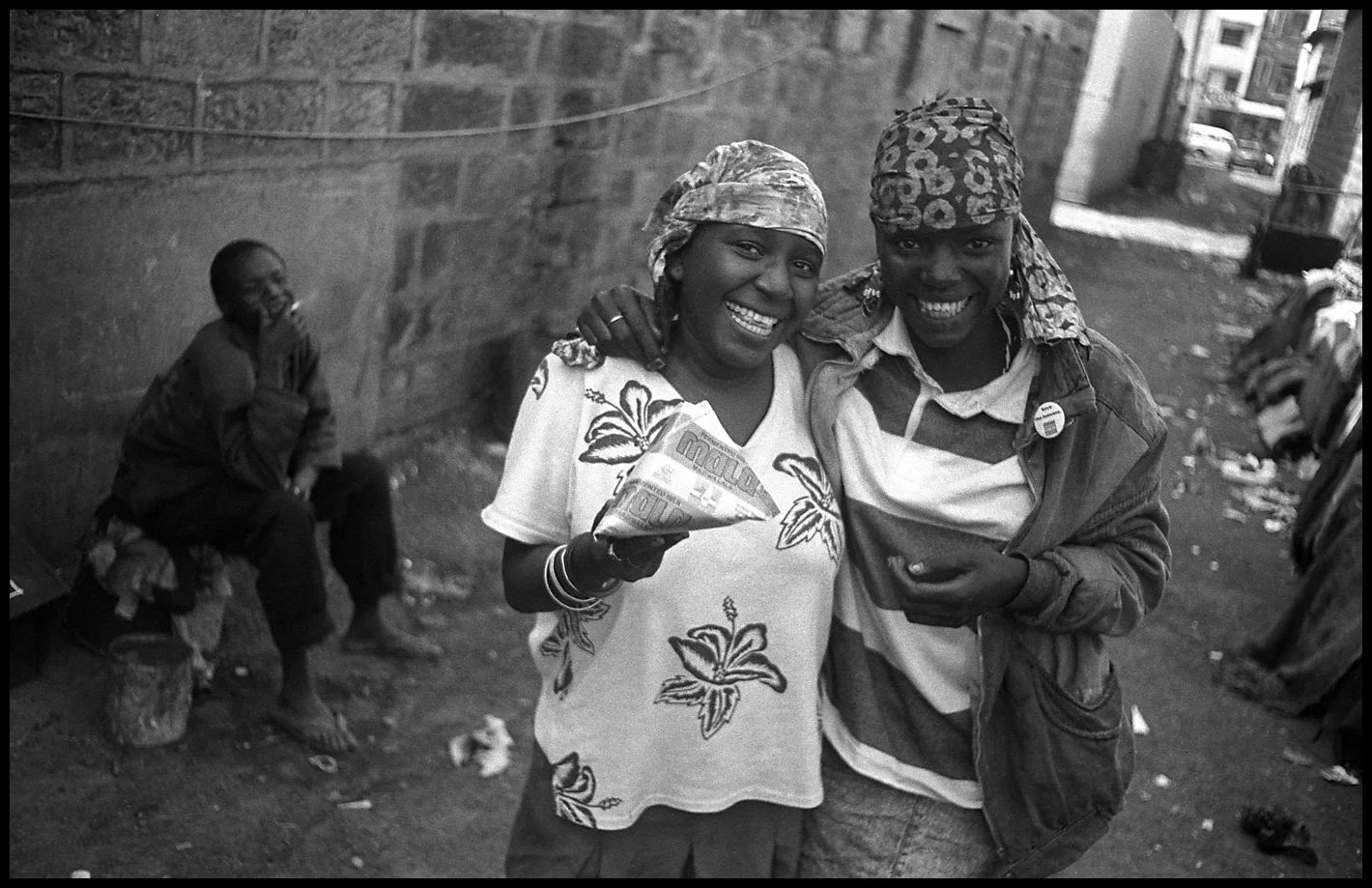

From the outset, an ongoing interest in the plight of street children had me haunting the streets of Nairobi, and to a lesser degree, Kampala. It became a personal project, often walking alone and regularly entering the slums and the makeshift alleyway communities known as chuoms to document the lives of hardened youth and their families. It was far from a feelgood experience. Soon after my arrival in Nairobi, I cringed in shame as I listened through a closed door while police beat a group of parking boys who had broken into the trunk of my car to steal a laptop computer my NGO had lent me.

Children in the chuoms, sometimes led by teens, had formed their own family units to replace those they had left behind. My memories of interacting with the street children are not done justice in these photographs. One of the most touching moments occurred when I was being followed out of the city open market by a group of kids. I handed out some fruit as we were walking. A few moments later I felt a tugging on my shirt, and turned around to find a sweet, barefoot and dirty little girl named Njoki offering me back half of the mandarin I had given her. My involvement eventually led to the Undugu Society of Kenya’s hiring me to supervise their information department, where I was able to advocate fulltime on behalf of the children and their families.