Hannah Wanjiru sijamsahau

Born in the fertile highlands of gichagi Central Kenya, but mired in the unforgiving, often brutal slums of Nairobi, Hannah Wanjiru was an enterprising, middle-aged Kikuyu woman, rising above hardship with cheer and optimism. We’d known each other for as long as I’d been in Nairobi, and enjoyed making each other laugh at our cultural differences. I had visited Hannah in Mathare Valley several times, knew her children and friends, and had listened to their many tales of bad luck and trouble. Long after leaving the NGO which had orignally brought us together in the mutual self-interest characteristic of most benefactor/beneficiary relationships, our friendship continued.

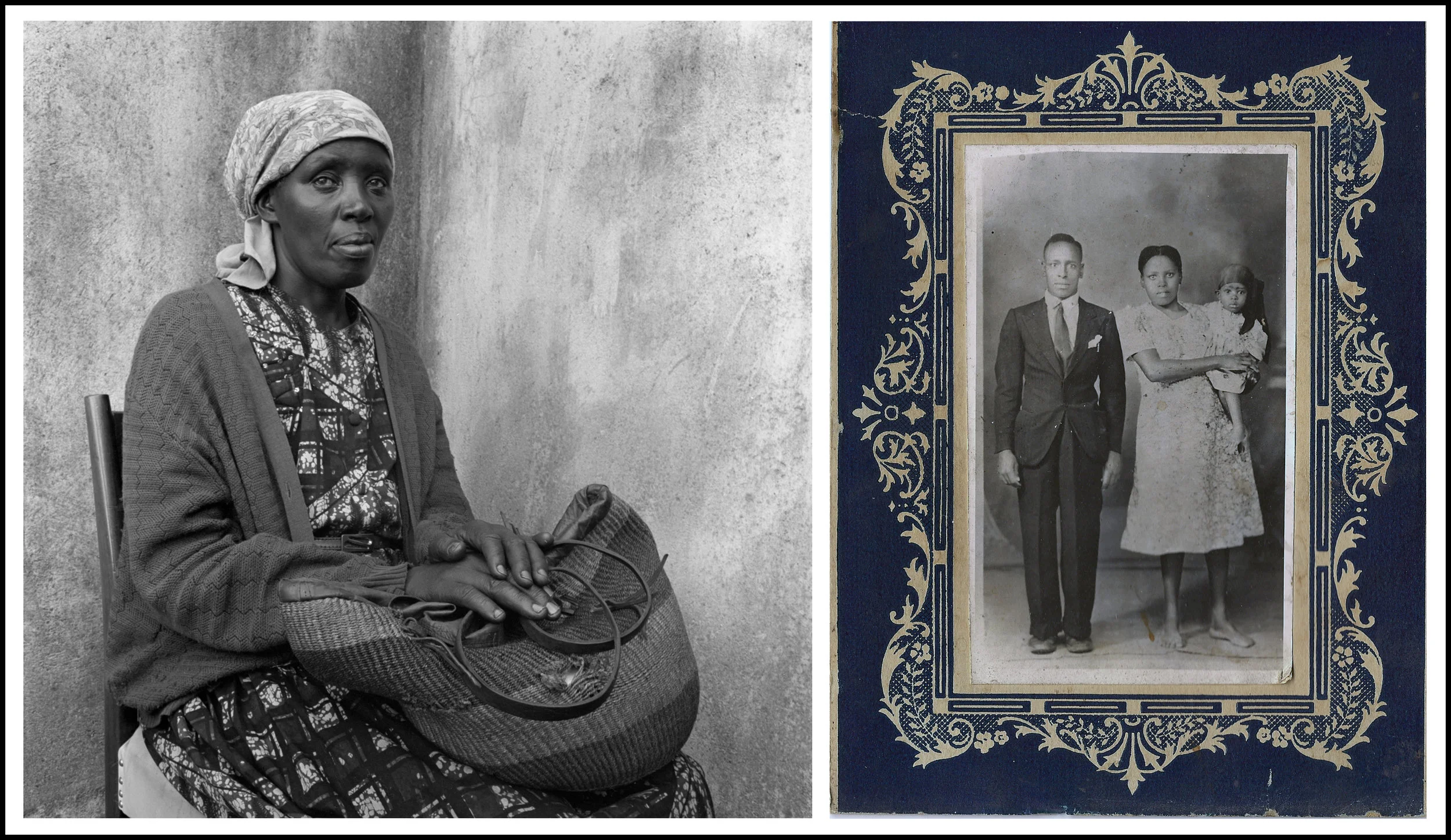

It was sometime in 1994, during one of her frequent visits to our darkroom in the loft of the French Cultural Centre, when Hannah surprised me with the unusual gift of a cheaply framed studio portrait of her as a toddler, with her parents. This wasn’t the first present she had brought me. The baby tortoise once pulled mischievously from her chiondo had become an unusual family pet at our flat in Westlands. But this was such an intimate gesture, and I was touched, if a little bewildered at her relinquishing what was by its nature something so deeply personal, and of which there was likely only one copy. Was this gesture, I wondered, somehow similar to the customary viewing of the family photo album? Why me? Although I never asked Hannah, I figured it was her way of showing thanks. Or that maybe she thought I’d appreciate it as a photographer. Or that I’d be better able to care for it than she could, given her tenuous existence.

Lacking appreciation for how popular and ubiquitous this style of family portraiture was in Kenya at that time, my initial interest in the photograph was as an object. The date 1945 was scribbled on the back, so I kept it, as an artifact with a perfunctory, historical quality. As portraits go, it is technically unremarkable; a grayish 3 1/2 x 5 print matted in an inexpensive, glassless 5 x 7 frame. The hand-made print had held up well, the black and white tones only slightly faded.

Years after returning to the United States, during post-graduate studies in Art Education, I eventually started to view this curious little portrait more critically, gaining an appreciation for its semiotic qualities. Seen in this print are vagaries of colonial cultural dissonance, notably the awkward attempt by Hannah’s father to assimilate into Western culture with a slight part in the hair, an ill-fitting suit buttoned too tightly at the stomach, a crooked shirt collar, and the jauntily protruding handkerchief. His stiff demeanor and uncertain smile make it easy to imagine that he had been dressed up specifically in preparation for this moment, to have his likeness recorded for posterity. In contrast, Hannah’s barefoot mother appears simple and plain, head uncovered, the faded patterns of the cheap cotton dress (her Sunday best?) an affirmation of her peasant status.

There’s nothing in the photograph to indicate that the cute, wide-eyed baby in this picture was in fact the hardened survivalist I had come to know, raising several children of her own, and now much older than her mother was when the picture was taken. Nearly a half-century old when it came into my possession, the frozen moment has since receded 20 years further into the past. A humble reminder of the sentimental value of photographic memories, its artless simplicity offers a break from the intellectualism that clouds unconditional appreciation. Hannah Wanjiru designated me as the guardian of her childhood memory, and if anyone reading this knows her whereabouts, tell her sijamsahau yeye.