Saba Saba

In July 1994, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada filed this report:

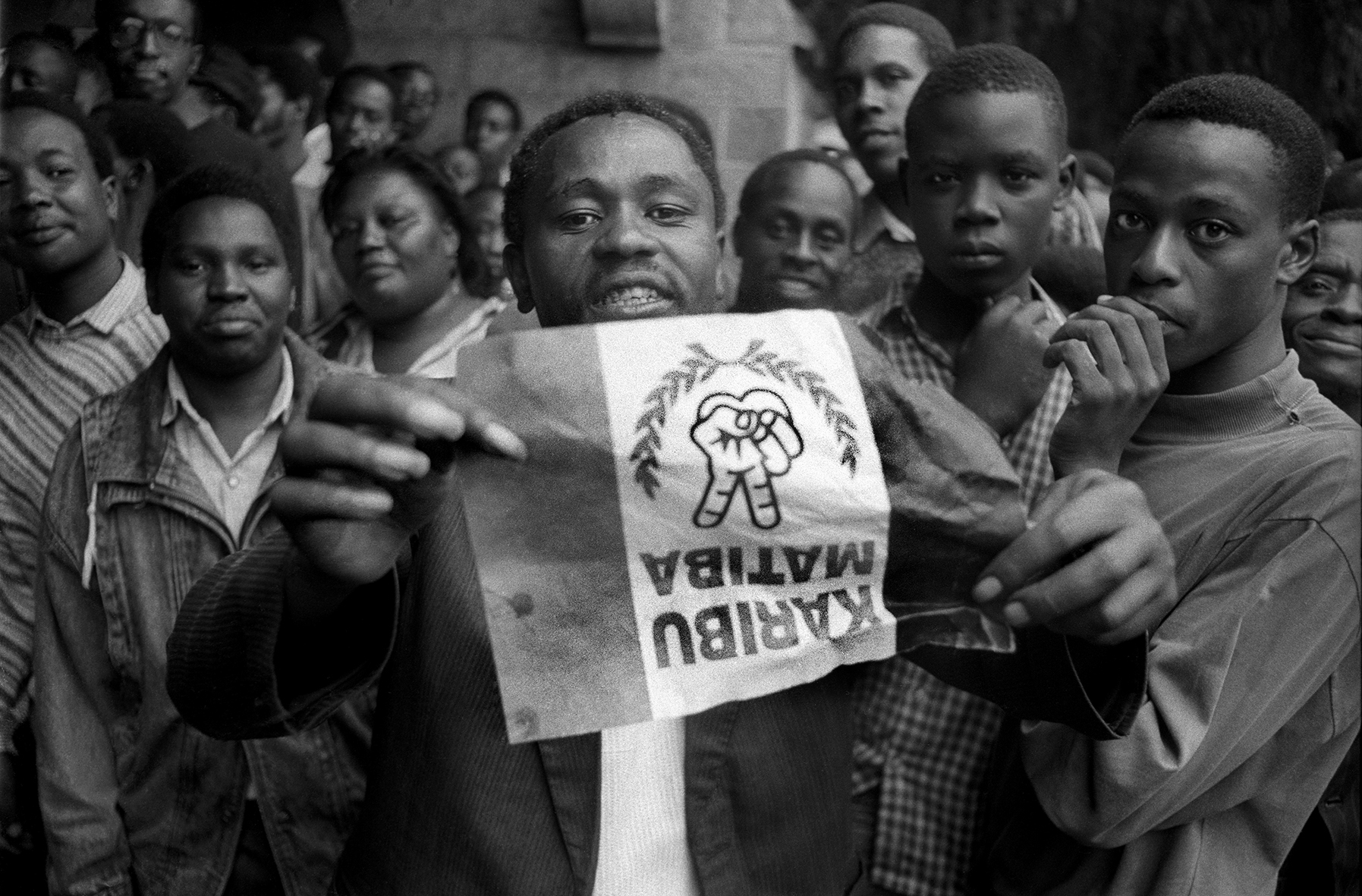

“Extensive riots were reported in Nairobi and other towns in Kenya during the first week of July 1990. The July riots were reportedly sparked in June 1990, when in an effort to silence political opposition and mounting criticism against government corruption and refusal to restore Kenya to a multiparty democracy, President Moi ordered the arrest of several reform advocates, including prominent opposition ministers, lawyers and former detainees.

“A pro-democracy rally organized by members of opposition groups at Kamukunji stadium in Nairobi was declared illegal. However, 6,000 people reportedly turned up and riots broke out when a contingent of police arrived in riot gear and began using batons and tear gas to disperse the crowd. The crowd responded by hurling stones at the police and stoning cars. Soon the riots spread to the outskirts of Nairobi, toward Majengo and Pumwani shanties and "the poor estates" of Dandora, Kariobangi, Kawangware, Kangemi and other towns of Kenya such as Nakuru, Muranga, Narok, Nyandarua, Kiambu, Nyeri and Thika. The riots reportedly lasted four days and left 20 people dead, many others injured, and more than 1,000 people in jail.”

During the height of the Saba Saba unrest (the Kiswahili nickname given for the seventh day of the seventh month), I had recklessly, out of pure political curiosity ventured into the city streets with a friend, and witnessed stampeding crowds fleeing the tear gas and batons of security forces. Njoroge and I took shelter in the upstairs foyer of an open building, and watched the melee through burning eyes. Later that evening the same curiosity found me driving down a side street in one of Nairobi’s poorer sections, where things were still chaotic. We were extremely lucky to dodge a few missiles thrown our way and get the hell out unscathed.

The next morning, upon hearing that the riots had been largely quelled, I felt obligated to return to the same neighborhood with my camera. The streets were deserted and I had barely the time to make a few exposures before I was swept up by police and taken into a local precinct for questioning. For two hours I sat on an old wooden chair across the desk from a grim-looking senior police officer. He wanted to know who I worked for, and what my reasons were for photographing in that particular area. The officer was unconvinced by my insistence that I was there on my own as an observer, and had no real outlet for my photographs. It was true— this was before I began contributing to Executive magazine, and the Kenyan newspapers had already been publishing excellent images of the worst of the rioting. As my nerves frayed, I heard myself blustering, “if you don’t believe (that I didn't photograph anything incriminating), take my film and develop it!” Trying to sound casual, I added, “If you find anything bad, you can kill me,” words I immediately regretted. The officer leaned in and asked me to repeat what I had said. He wouldn’t accept my attempts to dismiss it as an offhand comment, leaning in even closer and ominously insisting, “No, you said kill me. What did you mean by that?” Aware that there were at least two British journalists locked in this very precinct, I eventually managed to convince the interrogator that my motives were essentially apolitical. Finally convinced of my uselessness, the officer ordered two of his men to take me away. After what turned out to be a long drive to nowhere in particular, they dropped me off on the side of a road outside of town, after accepting an obligatory helping of chai, a small bribe no bigger than what a traffic cop might ask for if you ran a red light. I hopped onto the first matatu and made it back to rural Rironi without further incident, and later contacted Reuters to tell them about their detained employees.

The following morning some Kenyan friends and I took a walk to the Rironi marketplace, but were chased out by angry soldiers who were still patrolling, if not occupying, this typical Kikuyu village. On the way back toward our homes, government trucks could be heard rumbling, and then seen rolling toward us on the narrow strip of broken highway. My friends knew the worst could happen and did not hesitate to get me off the road. Fortunately we were near my home, and as we ran zigzagging, laughing and frightened through a neighbor’s tall corn, shots were fired in our direction.